BY SHEUNG YIU

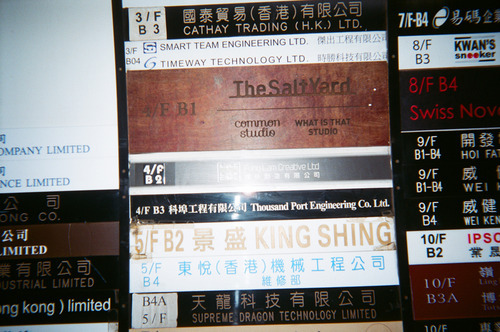

Ask anyone in the local scene to make a list of great photography galleries in Hong Kong, The Salt Yard’ will no doubt be on the top of that list. Since its founding in 2013, The Salt Yard has opened a portal to international photography, a platform for scholastic exchange in contemporary photography. Being photographers themselves, the founders hold a specific vision, persistence and aesthetics on selecting noteworthy photographic work, a spirit that is rare to see in the commercial art hub like Hong Kong.

Last Saturday was their last opening party. As usual, The Salt Yard had its opening party two weeks after the actual opening of its exhibition. It is one of the peculiar things about The Salt Yard. It opens its exhibitions on weekdays and hold the opening party on the weekend week after. ‘Some photographers insist on opening on weekdays despite the fact that most people come on the weekends, so we move the opening party to the weekends instead.’ Dustin once told me.

The Salt Yard

It is not a big space but it has everything a photo enthusiast wanted, an independent photo bookstore and a small photo book library inside a photo gallery. It was designed to be the place for artists to hang out and share ideas. It is compact but perfect. And if that was not enough evidences to indicate its greatness, perhaps the guest list of the farewell party would. Many significant players came to say goodbye, among them the Chairman of Hong Kong International Photo Festival, Alfred Ko, Japanese photographer HAL, recent Hong Kong Photo Book Awards Winner, Dick Chan and renowned local photographer Paul Yeung.

Dustin and I talked about the future for The Salt Yard. We talked about how difficult it is to get government funding and we whined about the lack of photographically-educated audience. The gallery is short-lived, but it has created something really special. The venue may be gone for now but the gallery will live on as an online independent photo bookstore.

What is your intention of opening an independent photo gallery?

The venue was originally a commercial studio of the other two founders, Lit Ma and Gary Ma. Later in their career, they did fewer commercial studio shoots and the studio was left vacant often. Since I had some experience in organizing photo exhibitions and writing photo essays, they invited me to start a photographic art project making use of their space. Obviously, the most straight forward way is to turn it into a photo exhibition gallery.

The Salt Yard

Why the name, the Salt Yard?

That has something to do with history. In the Northern Song dynasty, Kwun Tong was an royalty-owned salt pan. Also, we all grew up in this district and witness the changes in Kwun Tong. We wanted to plant seeds of culture here. We hoped to show that photography, life and culture coexist.

Which photo exhibition are you most satisfied with?

Every exhibition is our child, and each gave me satisfaction (or dissatisfaction). The one I am most satisfied with is when my exhibitions draw people who are not frequent visitors of photo exhibitions or galleries, such as ‘When Coast Lilies Are In Blossom’, a photo exhibition about the 311 Tsunami in Japan. An elderly whose daughter married away to Fukushima came to the exhibition. Seeing the photographs comforted him. The moment made me realised the intimate connection between photographic work and its audience.

11/12/2011 Shidoke, Haramachi Ward, Minamisoma City, Fukushima Pref.

“I want to come here to have a walk. I have been thinking of it for a long time.” I say hello to this man as I feel curious why he, a non-local, walking around in the quake zone.

21/9/2011 Morioka-ekimaedori, Morioka City, Iwate Pref.

A 17-year-old mother. She looks uneasy with a child in her chest. But then my heart feel warm as I find that the child does not mind at all and is sleeping well.

What is your vision when designing The Salt Yard, a unique photography exhibition space?

Right from the start, we designed the space with the audience in our minds. Instead of seeing The Salt Yard as the platform for artists, creatives and photographers to show their work, we wanted to nurture a new audience, we wanted to build a more lively experience to appreciate photography, so we designed a space for reading and opened a independent bookstore. We do not have a receptionist. We let the audience move freely around the space and explore, instead of being a passive viewers.

What is your philosophy on curating? Can you tell us about your curating process?

I selected photographers mainly looking at the completeness of their photo work. Another thing is we hoped to include photography from around the globe, so we strived for geographical diversity in the photographers we picked and their relationship between their societies, their cultures and their photographic art, for example, Shen Chao-Liang’s ‘Stage’ and ‘When Coast Lilies Are In Blossom’ by Japanese photographer Kazutomo Tashiro.

The Salt Yard

The Salt Yard

What problems have you encountered in curating photo exhibition that you have never thought of before hand?

There are a lot of trivialities in the daily operation of a gallery, small things like cleaning to installation of an art piece to promotion, every thing needs a lot of energy to take care of. My friends and I work part time in the gallery so time management requires extra careful planning. Budget and finance are also tougher than we expected. In addition to all that, since our venue is not the easiest to get to nor an art hub, we did extra work to promote our exhibitions via different media to inform public about our gallery.

How is your experience negotiating with photographers and agencies around the world to exhibit their work in an independent gallery?

Many of the photographers are very positive and even excited about exhibiting their works in Hong Kong. Nearly all the photographers we have ever collaborated with have never had any solo exhibition here in Hong Kong, even for Chinese photographer Taca Sui. Despite that, I still need to spend some time explaining the nature and the philosophy of The Salt Yard to them, especially those with representation by galleries or agencies. We are not a commercial gallery. We do not have any sales representatives to facilitate trading. My work is to make sure that they do not have an illusion of a strong marketing opportunity through our exhibitions. Also, they always have strict restrictions on delivering image files for media promotion which always gives me headaches!

Cover of the last exhibition at The Salt Yard, ‘Illusion’ by Shoji Ueda.

Any useful comment for aspired people who would like to start an independent photo gallery?

My advice would be: Think throughly before action. Hong Kong is not exactly the best place for art. Aside from expensive rent, do not overestimate public’s passion about photo exhibitions. Having great works is not enough, you have to be patient and ready to nurture audience’s ability to understand and appreciate photography.

Although the venue is closing, the e bookshop will keep running as a continuation of the photo gallery. Can you tell us what have you planned for the online photo bookstore. Should we expect an expansion/ collaboration?

In the past, because we need to organize exhibition, the time and resources we invested on our online photo bookstore is limited. I will spend more time on exploring relatively alternative and independent photo book publishers hereinafter. Commercial consideration is not the sole reason for running our bookstore, we see it as a different way to promote work, we see it as ‘book curation’. We may participate in photo book related promotional activities.

What is ahead of you, the three founders, after Salt Yard?

First, more time on running our online photo bookstore. This needs huge amount of work. Lit and Gary will go on with their photography career, and I wish to spend more time on my own personal photo project. I will keep curating shows in the future given the chance.

Salt Yard is an artist-run, independent photography gallery in Hong Kong. Founded in 2013, The Salt Yard has produced several significant photo exhibitions, including ’The Game is Killing the Game’ and ‘When Coast Lilies are in Blossom’, a series of large format portraits of residents hugely impacted by the 311 Tsunami in Japan. The current exhibition ‘Illusion’, featuring the work of Shoji Ueda, is the gallery’s last exhibition. The gallery will continue running in the form of online photo bookstore.

The three co-founders, Lit Ma, Dustin Shum and Gary Ng (from left to right)

Lit Ma’s Bio:

Lit Ma is the founder team of Common Studio, The Salt Yard and the contributor photographer for Monocle. He is also a photojournalist for numerous press and publications. He received education from Hong Kong Christian Kwun Tong Vocational Training Centre in 2000 and Received his Bachelor Degree of Applied and Media Art at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University in 2011.

Gary Ng’s Bio:

During the school years at Focal Point Visual Art Institute in 2003, Gary had already been working in the photography field, and mainly focused on commercial assignments. In 2009, Gary had moved back to Hong Kong from Vancouver and had started up Common Studio with Lit Ma, and in 2013, both had teamed up with Dustin Shum to create The Salt Yard.

Dustin Shum’s Bio:

A photojournalist for more than ten years, Dustin Shum now works as a freelance photographer. Shum has received many awards for outstanding documentary photography over the years, including those by the Hong Kong Press Photographers Association, and Amnesty International. In his work, Shum focuses on the relationship between individuals and urban spaces. In Jan 2013 he co-founded The Salt Yard, an independent, artist-run exhibition space dedicated to photography, where he curated a number of exhibitions by overseas and local photographers.